|

This article

originally appeared in World Literature

Today

WORLD

LITERATURE IN REVIEW: ENGLISH WORLD

LITERATURE IN REVIEW: ENGLISH

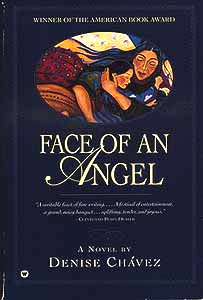

Denise Chavez. Face of an Angel New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1994. 467 pages. $23. ISBN 0-374-15204-7. "It's a long story," Soveida Dosamantes warns us in Face of an Angel, Denise Chavez's first significant literary work since The Last of the Menu Girls (1986); but tell she must so as to stifle disturbing memories, memories like "clothes in your closet . . . you never wear . . . afraid to throw out because you'll hurt someone." Soveida works as a waitress at El Farol Mexican Restaurant, the novel evolving as literary tribute to servants: Face of an Angel as Odyssey for the working poor; Chavez as Hazel's Homer. No Rodchenkoesque paean to the working class, Chavez's book is more Dickens Hard Times than Horatio Alger parable. Early on, we learn Soveida Dosamantes was named after a twenty-seven-year-old "pregnant woman with two small children" who was killed instantly in a car accident. Soveida's aptly named mother, Dolores (Spanish for "pains"), "read about it in an obituary' column . . . and like[d] the name. It stuck." Here, naming serves as a microcosm for what follows. Since Menu Girls, Chavez has developed her range, unveiling chapters eclectic and experimental. For instance, chapter 5 appears as two dueling prose columns retelling Soreida's parents' courtship---the form recalls more the theory of artsy French philosophers (viz., Derrida's Glas) than the stolid prose of American novelists (Vonnegut, true, plays with pictures). The expressionistic gap between Dolores Loera's and Luardo Dosamantes's testimony figures their fractious relationship. It also calls forth the border between men and women, between women and women (with class as allegorical emphasis), and between the United States and Mexico which found this tale. It is odd, perhaps incorrect, to imagine a border as "foundation," but for Southwest denizens it is a common truth. Other tactical quirks await Chavez's readers as she plants two texts within the text: one, twelve-year-old Soveida's autobiography; the other, The Book of Service, Soveida's guide for El Farol waitresses. As with all books within books, one ignores them at one's own risk: Soveida's manual teaches waitressing, but structurally it is more akin to the calendar in Twain's Pudd'nhead Wilson, striking the novel's thematic keynotes: "Life was, and is service, no matter what our station in it. . . . It is those to whom more is given from whom more service is demanded." Chavez writes a waitresses' rejoinder to Laura Esquivel's chef-centered Como agua para chocolate: not recipes proper, but recipes for service. Like Esquivel's recipes, Soreida's advice serves as primer for survival in the midst of personal crisis. Other maneuvers warrant mention. As with Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, within whose work one find evocative tributes to such early African American storytellers as Zora Neale Hurston, Chavez laces her novel with gestures at early and contemporary Chicano/Chicana writers. When Dolores tells Soveida, "Whatever you do, don't marry a Mexican," her words echo Sandra Cisneros's story with a similar name; Chavez's chapter 27, "The Honse on Manzanares Street," also recalls Cisneros's early Mango Street novella. When one thinks of Americans of Mexican descent, one does well to picture communities ordered by Catholicism and the family (its chief symptom). No surprise then to encounter Soveida, age twelve, ending her brief autobiography with a question worthy of Augustine: "So what am I? Saint or sinner?" Her answer, in the form of her life, is not conventional, and not very religious. The irony is hard to miss when we join Soveida in a Jesus shrine, where the son of God and man appears in a half-eaten tortilia. The Catholic Church is an easy target, but when not exposing Vatican broadcast inconsistencies, Chavez takes on the quasi-religion of Latino folklore fetishists, with Soveida eschewing sentimentality: "It's not surprising I didn't hear tales of La Llorona, La Sebastiana, El Coco . . . Papa Profe beat Mama Lupita, Tio Todosio liked the boys . . . our ghosts were real." Religion is out, the family dysfunctional; no long shot then that sex too is problematic; Chavez's novel soon evolves into a bestiary of sexual anomalies. Soreida's father Luardo, when not molesting her cousin Mara, is busy introducing his daughter to mechanical peepshows--one memorable opus featuring naked women washing cars. Oddly, Soreida's lascivious father proxies Chavez's position within the book: "Later, before I went to sleep for the night, he would tell me stories . . . about a little girl named Soveida." No room for comment on this loaded coincidence here. Familial dysfunctions notwithstanding, the most powerful glosses in the book are on relations between women, as when Soveida describes the volatile bonds linking grandmothers, mothers, and daughters: "Only Dolores could hear the piercing decibels that brought her pain, the pain of a dog unused to certain soundless whistles. These were words from one woman to another, a mother to a daughter. . . . They were damaging[,] scarring words. Welts underneath clothing . . . from . . . one who knows your most intimate smell. Words from a woman who sees you as the man who makes love to you would. A mother." In sum, Chavez's novel is an antisentimental family history--less Cheaper by the Dozen than As I Lay Dying. The book is an open mouth giving voice to open wounds. "This sex which is not one," Luce Irigaray put it in her landmark essay; Chavez fashions a prose sister-text. One hears also the echo of Rosario Castellanos. AS the novel closes, our hardworking waitress is pregnant. Soveida calls her child "Milagro" (Miracle), one "won't be like the women I always knew: lonely, clinging, afraid." The last word here goes not to Chavez but to Sandra Cisneros, whose

witty, back-sleeve promo blurb solicits the patronage of both writers:

"I love this book so much it sounds like I'm lying."

William

Anthony Nericcio

Copyright of World Literature Todayis the property of World Literature Today and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Source: World Literature Today, Autumn95, Vol. 69 Issue

4, p792, 1p

|