|

This article

originally appeared in World Literature

Today

WORLD LITERATURE IN REVIEW: UNITED STATES

If genres were household accessories, autobiography would be a gilded mirror; and readers of Richard Rodriguez's Days of Obligation, the right-leaning, gay, Chicano curmudgeon's second autobiographical essay collection, will peer often into Rogriguez's mirror, an existential toilette of sorts. The subtitle misleads, "Argument" positing contentious dialogue. The collection, however, is less dialogue than monologue. Accordingly, Johnny Carson appears as motif. Ostensibly a walk among tragedy, comedy, Catholicism, ethnicity, and education, Days of Obligation speaks of and to Latinos/Latinas (especially Californians). A savory memoir filled with curious erratic takes, Rodriguez's "book" sutures essays which appeared in Time and Harper's among others (and on TV on the BBC), continuing where Hunger of Memory left off: moody "Ricardo" laments his indigenous physiognomy while spewing right-wing annotations of U.S. decay--E. D. Hirsch in brownface: "No one in my family had a face as dark or as Indian as mine. My face could not portray the ambition I brought to it." Rodriguez's alienation here is painful and poignant, but we need not let it silence our critical intervention. Angst has ofted shrouded the bitter piquancy of the iron animus. The irony of Rodriguez as spokesperson for Mexican and Latino issues is almost too obvious: "A man . . . with his back turned to Mexico, now I am to introduce Mexico to a European audience." This gives some pause: a telepersonality for all things Chicano/Latino broadcasting cultural "realities" via his tortured soul's fractious lens. How fractious? "[I was] repelled by Mexico's association with the old. In my imagination, Mexico was a bewhiskered hag." Rodriguez knows his perspective is skewed, yet he speaks. The seduction of the telemirror beckons. "I lower my eyes. I say to Mexico . . . I cannot understand you," Rodriguez writes. Confirmation follows: "Mexicans move as naturally and comfortably in the dark as cats or wolves or owls do.... Mexicans get drunk and sing like cats beneath the moon." Readers wash in a warm, fetid bath of cliche. So Rodriguez takes us with him to Mexico, where comfort is not at issue; there we encounter a "Lifestyles of the Rich and Mexican American'" with an American credit-card company "protect[ing]" Rodriguez, paying bills and booking tours for our "haute bourgeoisie" representative. But this is Mexico City. What of the border? Traveling in Tijuana, Rodriguez will not drink the water or eat its "unclean enchantments." Presently, Rodriguez works with a priest in an underdeveloped neighborhood; he adds, "What a relief it is, after days of dream-walking, invisible, through an inedible city, to feel myself actually doing something." This does not last. Soon after, distributing pastries following a mass, Rodriguez finds himself assaulted: "Now the crowd advances zombielike.... Silent faces regard me with incomprehension. An old hag with chicken skin . . . grabs for my legs." Recalling the reference above to "Mexico" as "old hag," we sense our Mexican American guide's internalization of California's visceral fear of Mexicans. Rodriguez is just as ambivalent about his homosexuality. He watches as AIDS volunteers are recognized at the front of his local church. Most volunteers advance save for redoubtable Richard: "These learned to love what is corruptible, while I, barren skeptic, reader of St. Augustine, curator of the earthly paradise, inheritor of the empty mirror, I shift my tailbone upon the cold, hard pew." Rodriguez reveals again his "unwillingness to embrace life," hoping, one imagines, for expiation via textual disclosure. It is existentialism redivivus Sartre sans salsa. As Rodriguez's "soul is the bathroom mirror," we are not spared personal insights from his morning wash. On literature: the "university is dismantling the American canon . . . in the name of my father [and] of Chinese grocers and fry cooks, disregard[ing its] Judeo-Christian foundation." On civil rights: "As America became integrated, the black civil-rights movement encouraged a romantic secession from the idea of America." On academia: "Gay studies, women's studies, ethnic studies--the new curriculum ensures that education will be flattering." It gets worse. Our brief tour concludes with Rodriguez on el movimiento Chicano, whose activists "insisted on a rough similarity between the two societies--black, Chicano--ignoring any complex factor of history or race that might disqualify the equation." Ah, hindsight's acuity, here with astigmatism. It was a sensitivity to matrixes of history, race, gender, and class joined with a demand for constitutional justice which sustained sixties Chicano activism. Richard Rodriguez's new book rehearses a Chicano, fin-de-siècle Narcissus. Like some mutation born of Roy Cohn and Jack Webb, our self-loathing/loving narrator polices the precincts of the Americas. Readers marvel as we await Rodriguez's tragic fall (simulcast nationally), his declared attraction to Milton's Satan echoing throughout. A Mexican-American who seethes at Chicanos, a gay man who sets himself apart from gay men, an English scholar who leaves the academy. I envision Rodriguez's next book: on the cover, Rodriguez's face in a mirror (pensive); looking back, a horse--with Richard's eyes and soul (our Chicano Houyhnynm: Rodriguez as Gulliver, estilo latino). But this is less than kind. Better to allow Rodriguez

his own denouement. Surrounded by mirrors in a San Francisco health club,

Richard whispers: "Behold the ape become Blakean angel, revolving in an

empyrean of mirrors." Now let the mirror fall.

William

Anthony Nericcio

Copyright of World Literature Today. The property of World Literature Today and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. World Literature Today, Winter94, Vol. 68 Issue 1,

p141, 2/3p

|

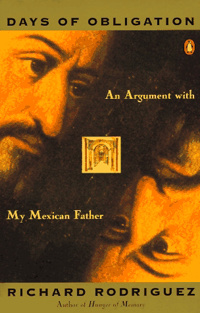

Richard

Rodriguez. Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father.

New York. Viking. 1992. xix + 230 pages. $21.

Richard

Rodriguez. Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father.

New York. Viking. 1992. xix + 230 pages. $21.